(Tips: if you hover over the photos, you’ll see a caption. You can double click on a photo to enlarge it.)

It has been a week and a half since we left Samoa, perhaps my favorite country I’ve visited thus far due to it’s cultural uniqueness, warmth of people, and natural beauty. The moment we stepped off the plane in Upolu, Samoa, we were greeted by a band playing traditional music in the airport, gracious customs and cab drivers milling about, laughing and joking in a contagious way at 6:30 am.

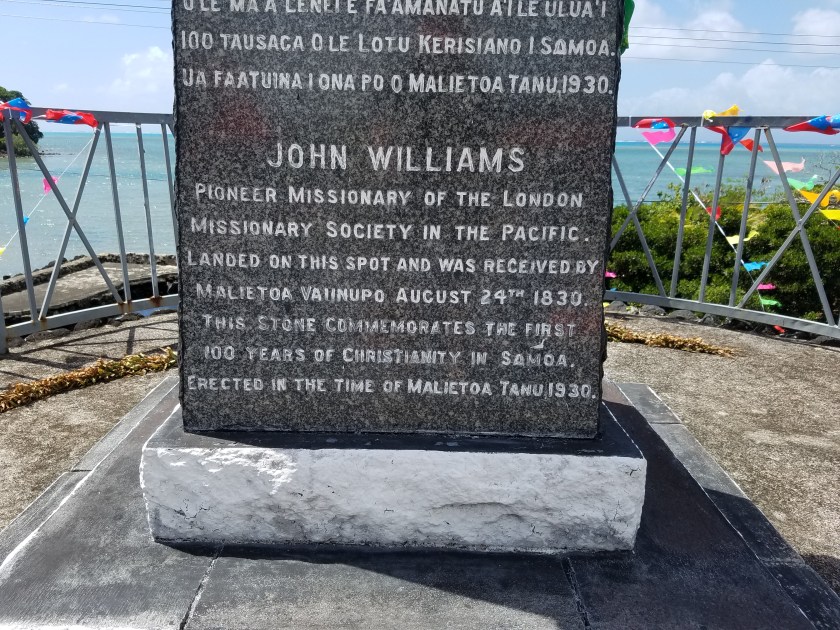

Samoa is a strikingly beautiful country with its hills sloping onto white sands, merging with turquoise waters. It has remained quite true to its cultural origins. Family is at the crux of Samoan culture, as demonstrated by every home having a fale (pronounced fah-lay), an open aired structures with a roof, floor, and posts. Fales in front of peoples’ homes are large, allowing a place for any visiting family member to stay and sleep. (There is a Samoan saying that translates into “many family members make the load lighter.”) Tribal and community meetings are held in fales as well, with a very specific seating arrangement for the chief and leaders. There are many small fales along the beaches to relax in, get some shade, and even spend the night. We somehow all failed to get a photo a large one, though there is a photo at the end of this page of Helen in a quite rickety one. Samoa is also filled with more churches than I have ever seen in any country, having been hugely influenced by early missionaries.

Our Samoan experience was especially rich due to our gracious and knowledgeable guide, Tai. He drove us safely (the driving is quite scary on the island!) to so many beautiful sites, all the while sharing his knowledge of the country’s culture, history, ecology, and politics. Tai, age 35, is a devout Christian with a very big heart, and a great deal of responsibility as chief of three villages. We asked to attend church with him, eager for experiencing life in Samoa. It was a small Potter’s Pentecostal church with a band consisting of two guitarists, a drummer, keyboard player, and two vocalists. The lively music made up for a smaller congregation. We found the members very real and inviting, without judgement or expectation from us.

Our first few days were spent swimming in cave and fresh water pools, feeding some sea turtles, visiting several waterfalls, seeing amazing volcanic blow holes spray sea water higher than a coconut tree, walking/hiking, some snorkeling, and visiting the museum/home of Robert Louis Stephenson (author of Treasure Island, and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.)

On our third day with Tai, he showed us how to make coconut cream. We went to his home (just next to our Airbnb) where he, his wife Ellie, and their 10 year old son Des welcomed us. We watched Tai take ripe coconuts, put them on a metal stake to pull the husks away, crack the coconut in two, then grate the meat from the shell. We all had a turn at husking and cracking, but it was Tai who made quick work of it all, grating the meat from six coconuts into a bowl. He took a bundle of very thin, dried banana leaf strings forming a cluster that he then put the coconut meat in, squeezed, and extracted the cream from. Who knew that coconut cream didn’t come from a can??

An hour later, he and his wife and son came to our place as planned with a beautiful bowl of coconut cream rice, and a large kettle of lemongrass tea. With some vegetable platters I added, we had a delicious feast and a lovely evening with his family.

The next day we took a ferry from the island of Upolu, Samoa to the island of Savaii, Samoa. Tai also came to the island, where his in-laws live, so he could once again guide us. We went to his wife’s family’s home, where his mother-in-law Pali (pronounced Polly) was weaving a fine mat. This long mat you see below might take a month to weave, and would bring about $5,000 Samoan Talas (about $2,000 USD) to the family. These mats are used for special ceremonies, such as weddings and funerals. Tai also explained the etiquette of seating arrangements in a fale, where we watched Pali weave.

Tai’s 18 year old cousin Tao demonstrated coconut tree climbing; he looked up a very tall tree (perhaps 3 stories high), put his machete in his mouth, wrapped a sarong half way around the tree to loop his feet in, and proceeded to pull himself up the tree with impressive strength, ease and grace. He knocked down several coconuts, slid down the trunk, widdled a sharp stick he placed in the ground where he then husked each coconut and created a small opening in the “mouth” of the coconut face for us to drink the fresh liquid from.

Tai then showed us some interesting sights in Savaii, including the sapia cloth being made. This is a traditional cloth made of wood branch that is cut, peeled and then pounded repeatedly, making a very thin fabric. It is dried in the sun, then layered with a natural glue into a sheet of cloth, sometimes small for decoration, and sometimes large to make a dress or a wall hanging. A design is painted on it using a brush also made of wood, pounded at one end to spread its fibers into a painting tip. The ink used is made of a dye from the tamarind plant. When we left Samoa, Ellie and Des gifted us one of these cloths made in Ellie’s village.

The next day we joined Tai and his cousin Tao and for a 4 mile walk to his wife’s family plantation, full of coconut trees and a dozen cattle. Along the way Tai pointed out many trees, plants and some birds, including a fruit bat (which they call a flying fox), cocoa plants (which have a cluster of large seed pods coated in a slippery, sweet flesh), jungle rose, breadfruit, island flame, and many more species. Tao playfully made a wind spinner/pinwheel from a coconut frond, and a walking toy from a seed pod pushed along by a stick, both common toys kids would play with. Tao again climbed a coconut tree and knocked down a dozen coconuts, which he prepared for us to quench our thirst. He and Tai then took some of the coconut palm leaves and wove two baskets to carry coconuts and cacoa plants back home, in preparation for the umu we were to have. When we finished our walk, we cooled off in a spring fed fresh water pool. It was one of many that are on the side of the road available for anyone to use free of charge.

Later that day we had the amazing experience of participating in a traditional umu, a meal cooked in extremely hot rocks. A “size 2” (their name for a small roasting pig) had been killed and prepared by Tao; it was a notable juxtaposition to see an adorable piglet running around as a pet while one just a bit larger was awaiting the fire. Tai and Pali showed us how to scrape taro root, husk/peel green bananas, prepare coconut cream in taro leaf, and clean coconut shells to make a bowl. Ella and I had a turn at most of this, while Doug fished and Helen played with 7 year old Twy, Tai’s niece, who seemed delighted to have company and a girl she could box with. Though Twy spoke minimal English, the language of play is universal. Such was the case with Pali (Tai’s mother-in-law); her impish, playful spirit, and wry facial expressions was all that was needed to feel a connection and eliminate the need for a common spoken language.

The umu fire is made by first placing strips of wood and leaves in a square created by logs, which are later removed. Once a roaring fire catches, rocks are placed on the fire. When the cook has decided the rocks are hot enough the rocks are removed and the pig, banana, taro root, wrapped taro leaf with coconut cream, and fresh fish (thank you, Doug!) wrapped in foil are placed directly on the coals. This is all then covered with large banana leaves and cloths to hold in the steam, and some coconut shells with canned fish and coconut cream cook on top. The cook decides when the food is ready to eat based on how hot the rocks were at the start. In this case, it was about 40 minutes after the food began cooking when we then removed the covering and rocks from the food.

We were welcomed to their outside table where we filled our plates woven from coconut fronds by Pali. In standing with tradition, our fingers were our utensils, and the hosts waited to eat until their guests were well into their meals. Our favorite dish was by far the coconut cream in taro leaf, a Samoan delicacy. The leaf was very soft once cooked, like a spinach leaf, with the flavor of coconut cream, salt and a bit of onion–delicious! I wasn’t as fond of the pork; this may have been partially due to watching the preparation of the pig stuffed with hot rocks and mango leaves, causing smoke to spray from every orifice, or perhaps the adorable little pig walking around the table while we were eating. Samoans treat their animals well, and I felt much better about eating meat there than in the States.

Tai’s sister-in-law Siu joined us at dinner for a mug of cocoa that Pali made with the cocoa beans we collected that day. The beans are roasted, boiled, then mashed into a paste in hot water. Add a touch of sugar and you have delicious cocoa–the best! The entire family social scene, exotic food and tropical breezes made for a magical evening we’ll never forget.

The next morning Siu guided us to the remarkable lava fields created by volcano flow between 1905-1911. She pointed out the “pillow tree”; the downy material in the seed pods is used for pillow stuffing. We stopped by a couple of monuments with enough time to enjoy another meal at the Savaii Hotel and hop on the ferry back to Upolu, where we were greeted by Tai once again. When he brought us to the airport the next day for our departure to New Zealand, we were truly sad to say good bye. He gifted Doug a traditional necklace of large seeds painted with red dye that he’d made and we’d admired previously on him.

For anyone interested in my simple (and likely flawed) account of Samoan history, here’s what I recall: In 1899 Britain, United States, and Germany all had interest in ruling Samoa; the USA for the military base, Britian because they’d ruled nearby New Zealand and Australia, and Germany for the islands’ coconuts and cocoa (they’d brought many indentured servants from China and the Philippines to work). There was great tension between these countries, so the Samoans–who had long since become devout Christians due to the missionaries converting most islanders–prayed for a peaceful solution. This came about through a cyclone that wiped out all of the ships (with the exception of one British ship that managed to flee the harbor.) Starting back at square one, the three vying factions came to a solution: simply put, the British were told their fleeing demonstrated their lack of commitment to the island, so the Germans and Americans split the Samoan islands into German and American Samoa. There is still an American Samoa, with a large military base.

During WWI the New Zealand troops came and skirmished with the Germans, who decided they were too far from their homeland to fight for Samoa, thus German Samoa became what is now Independent Samoa. This was not without a fight, as New Zealand attempted to dominate Samoa for the next 25 years. In the early 50s the Samoans protested and some important Samoan leaders were assassinated, but ultimately Samoa gained independence.